The Contemporary Ragpicker: Hoods, Heels and Hip-Hop

This image-led research file will investigate femininity in hip-hop culture through fashion. Using images of Lil’ Kim and Missy Elliott as principle contrasting case studies, I will explore what femininity means to different female rappers and how garment design reflects this. First, I will outline what hip-hop culture is, its importance in contemporary society and the genres relationship to gender and race relations.

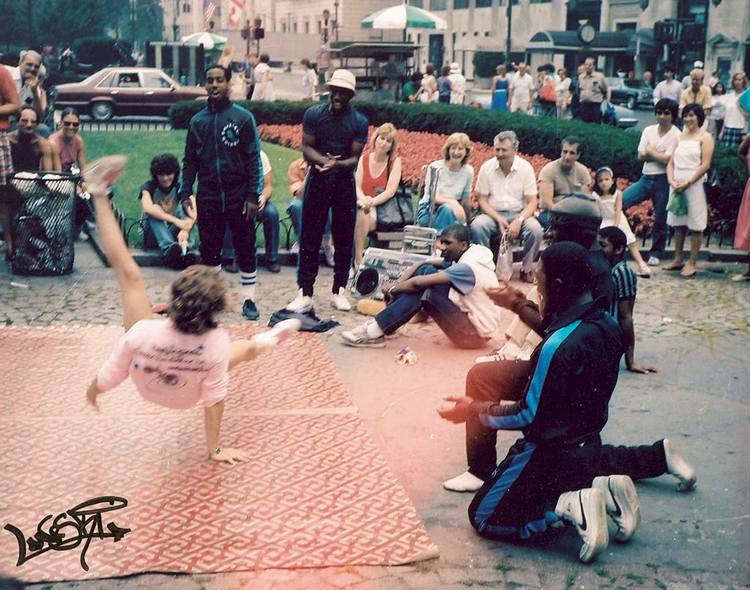

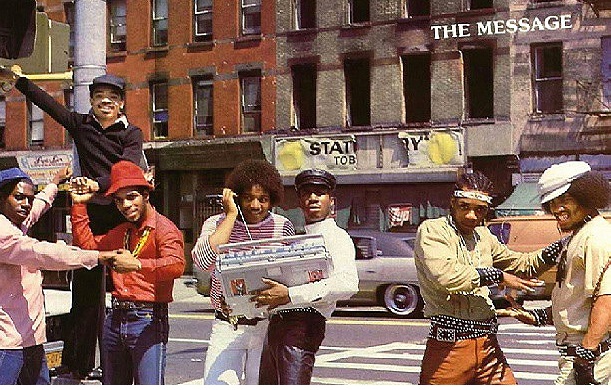

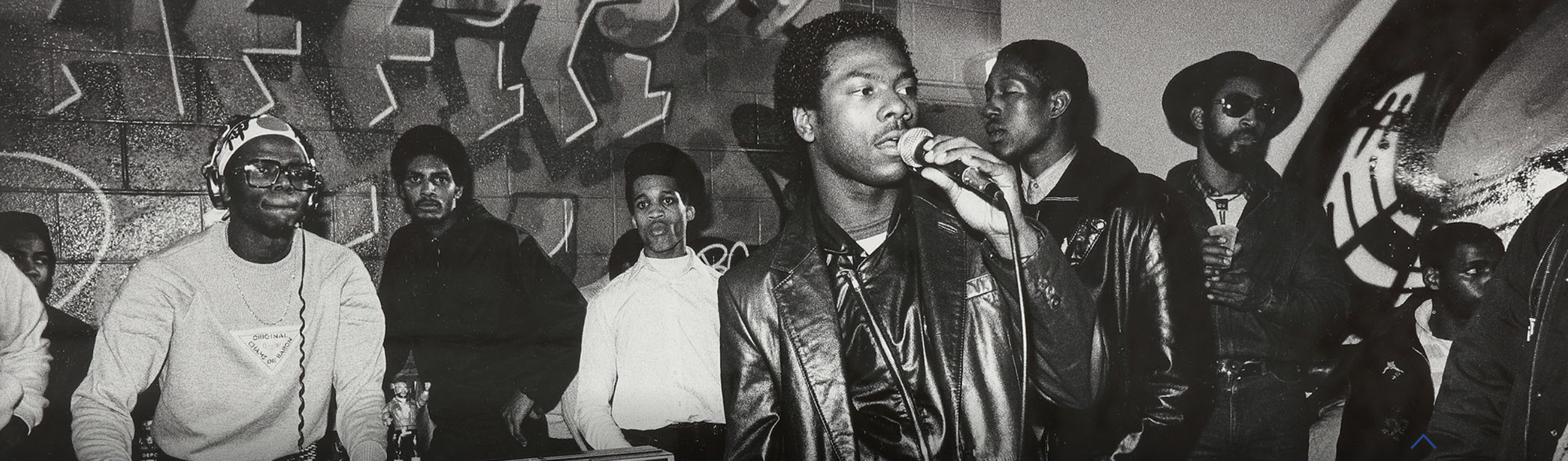

The intercontinental, multi-generational, cultural phenomenon that is hip-hop can be described as an umbrella term, which encompasses four artistic elements: graffiti, b-boying (or breakdancing), DJing and MCing. The popular music genre within its intersectional cultural form has abundantly dominated contemporary society and continues to command the creative industries through production of music, fashion, art and dance, as well as shaping the urban vernacular landscape. The genesis of hip-hop arose in the Bronx, New York during the 1980’s, the genre was incepted as a ‘voice and vehicle for political, social and self-expression’ by socio-economically deprived individuals within urban African American communities and ghettos. Hip-hop transpired ‘Amid the ruble of deindustrialization and the wholesale abandonment of the inner core of the city- not idleness or a lack of a work ethic’, the culture grew from a tool and creative vehicle for marginalised voices ‘to a mainstream multimillion dollar global industry’.

The endeavour to challenge and denominate ‘racism, education, sexism, drug use’ through ‘rhythm and poetry’, as well as creative practices like garment design has been met with consistent criticism, following its stereotypical disparaging anti-social characteristics. Hip-hop’s transgressive enclaves of production and performance cultivated in ‘parks, street corners, and city blocks’ challenged socio-cultural and financial exclusion by occupying public space, thus transforming the built environment. The transformation of public space into a performance space where ‘streets are transformed into locations to stop and gather, remaking and repurposing the built environment.’ is reminiscent of a larger societal shift in wealth and engagement in culture. In Peter Wollen’s ‘The Concept of Fashion in the Arcades Project’ he argues that ‘Fashion is the crucial element of the social superstructure’, garment design and wearing being an embodiment of a larger social framework working within gender, class and race. Wollen based his indagation off of Walter Benjamin’s meditation that “The economic conditions in which society exists are expressed (but not reflected) in the superstructure,” despite awareness that “things have gone out of fashion” and continue to do so we constantly partake in novelty, commodity culture. Which is where ‘we encounter the image of the ragpicker, who searched what has been discarded in order to return it, made new, back into circulation’. The repurposing and remaking of New York’s built environment is reminiscent of Walter Benjamin’s notion of the ragpicker, particularly when applied to hip-hop fashion.

However, within this alternative public sphere or ‘black counterpublic’ women have historically been excluded from hip-hop sites of production, as a result of the image of gender inferiority in the culture as women possess a ‘sexually demeaning, and provocative role’.

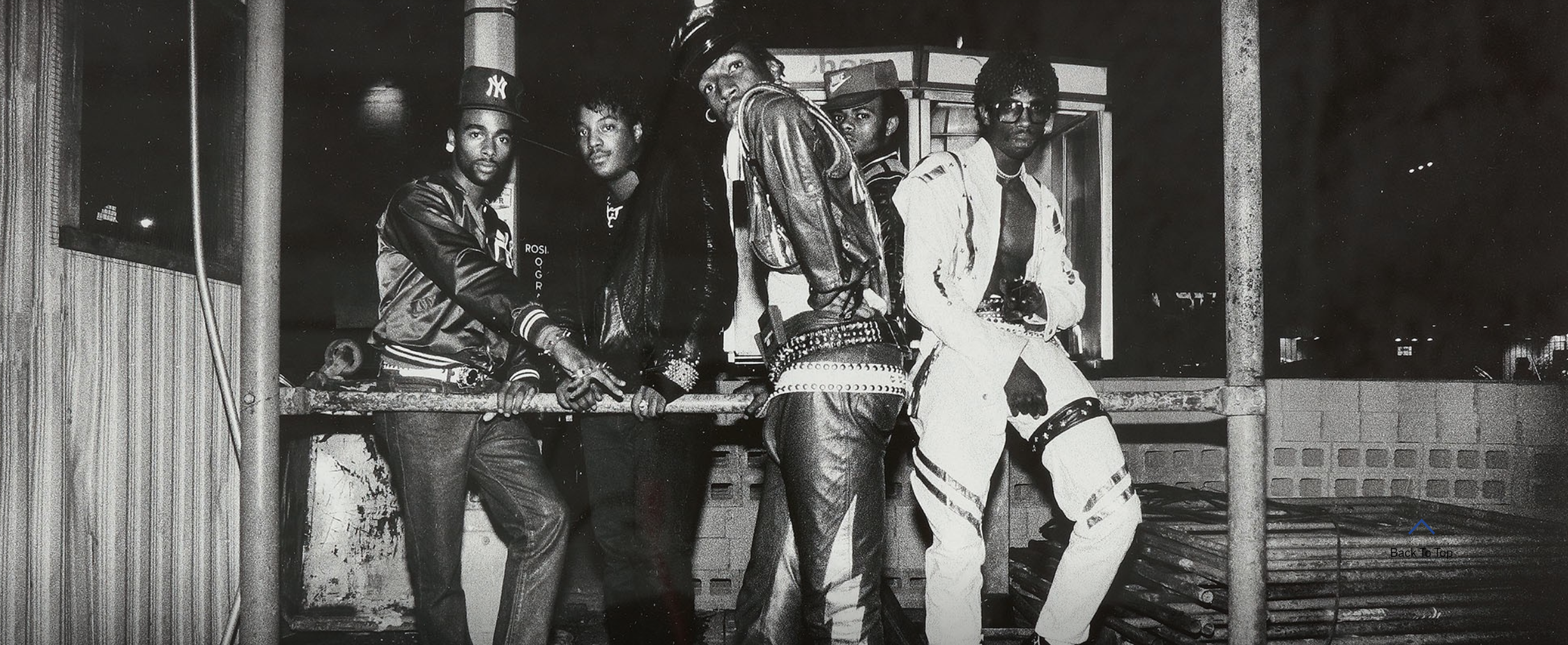

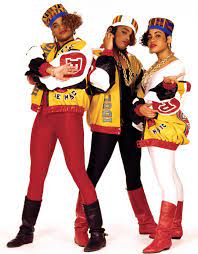

Women have comprised pivotal roles in the cultivation and continual success of hip-hop culture, despite an acute number of MC’s and DJ’s, they’ve confronted ‘racism, gender discrimination and classism’ to produce a distinct narrative of access, disregarding gender norms and oppression. MC Ms. Melodie attests this motivation to ignore exclusion : ‘Females were always into rap, and females always had their little crews and were always known for rockin’ house parties and streets or whatever, school yards, the corner, the park, whatever it was’. Figures such as Queen Latifah, Lil’ Kim and Missy Elliot subvert the expectation of women in hip-hop culture through different means but reach the common objective that masculinity and hip-hop are not synonymous, collectively they use lyricism in their music, as well as fashion choices to accent this. Although there are multiple archival hip-hop fashion styles, name-brand sportswear and tracksuits, as well as trainers like the Adidas superstars and Converse Chuck Taylor All-Stars, accessorised with ‘heavy gold jewellery’ have endured different eras and locational clusters of hip-hop’s participants. As a result of the exploration into afrofuturism and alternative mediations, ‘Fezzes, kufis decorated with kemetic ankh, kente hats, Africa chains, dreadlocks, and Black nationalist colors of red, black and green became popular’ with groups like the Zulu Nation and rappers like KRS-One. A fracture exists between male and female hip-hop fashion, but subsists even more so between female performers, on one hand female rappers like Lil’ Kim wear overtly sexualised, glamorous garments, whilst MC’s like Missy Elliot choose clothing distinctly more masculine thus subverting the expectation of hyper-sexualised female figures in hip-hop.

This photo taken by Janette Beckman for ‘PAPER magazine’ for a 1988 photo shoot features a group of eleven female MC’s, all wearing tracksuits, most branded with Fendi, Gucci and Louis Vuitton monograms. Notably, each MC is wearing prominent gold jewellery, emblematic of the wider musical afro-diasporic community. Additionally the majority of the female rappers in this image are wearing limited makeup and trainers, providing evidence towards the collectivity and collaborative relationships that existed between women in hip-hop, both musically and culturally. Aforementioned author, Peter Wollen argued that ‘Fashion can differentiate its wearer from the norm or, through imitation, it can assimilate its wearer into a group. The individual can be either an original, an initiator of fashion, or a copycat, a dedicated follower of fashion’. In the case of this image, fashion and garment assemblage assimilates the female rappers to each other and to the wider hip-hop community.

The image of notorious hip-hop group ‘A Tribe Called Quest’ both mirrors and contradicts the photograph taken by Beckman, reflective in its subject point of capturing an African American group of hip-hop participants. But contrasts in the non-uniformity of the styles, fabrics and shapes worn by the all-male group, instead of all wearing a uniting garment, like the tracksuit, we see Q-Tip wearing a denim jacket and jeans, and the other members wearing contrasting multi-patterned shirts, leather jackets and flat caps.

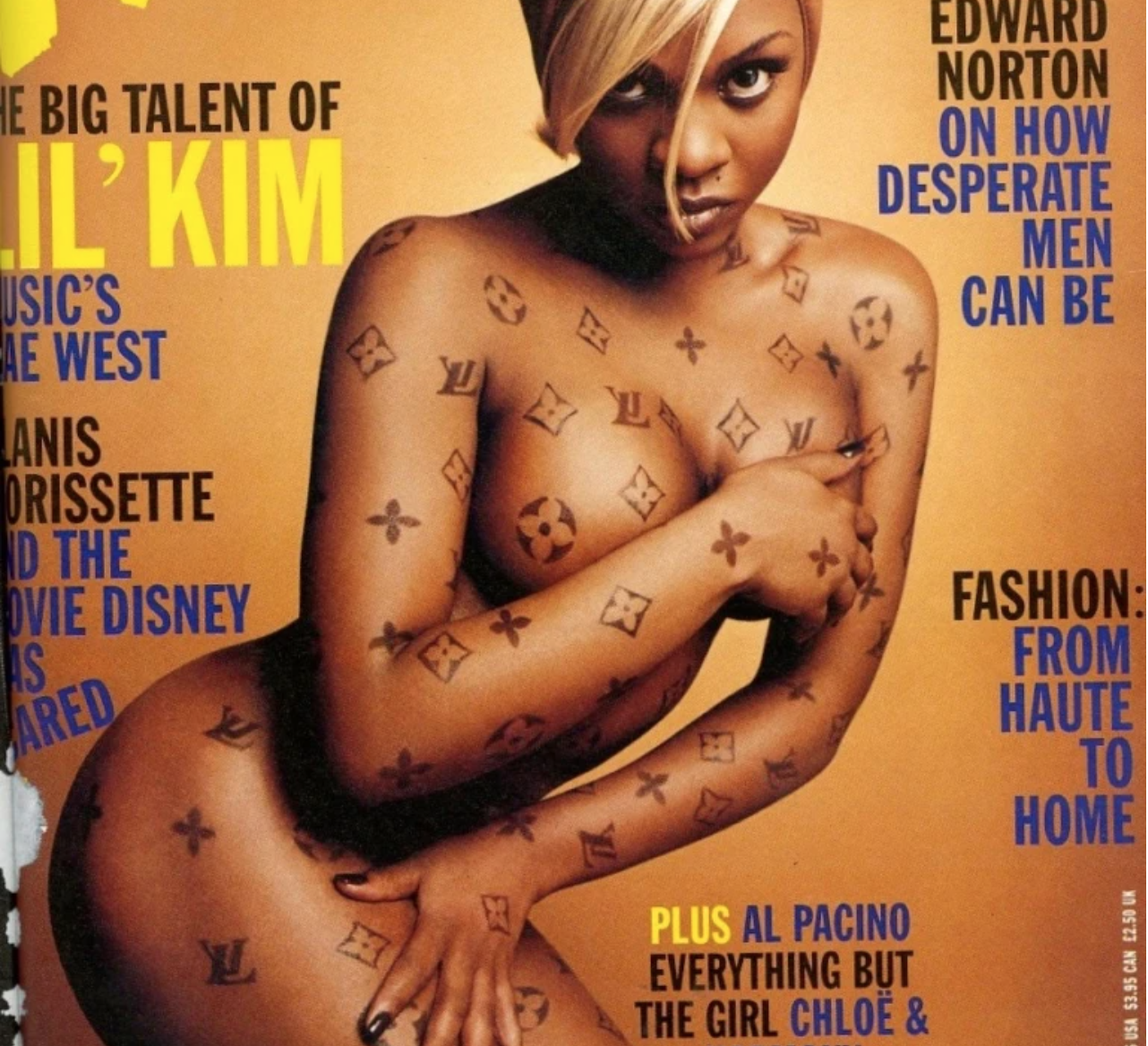

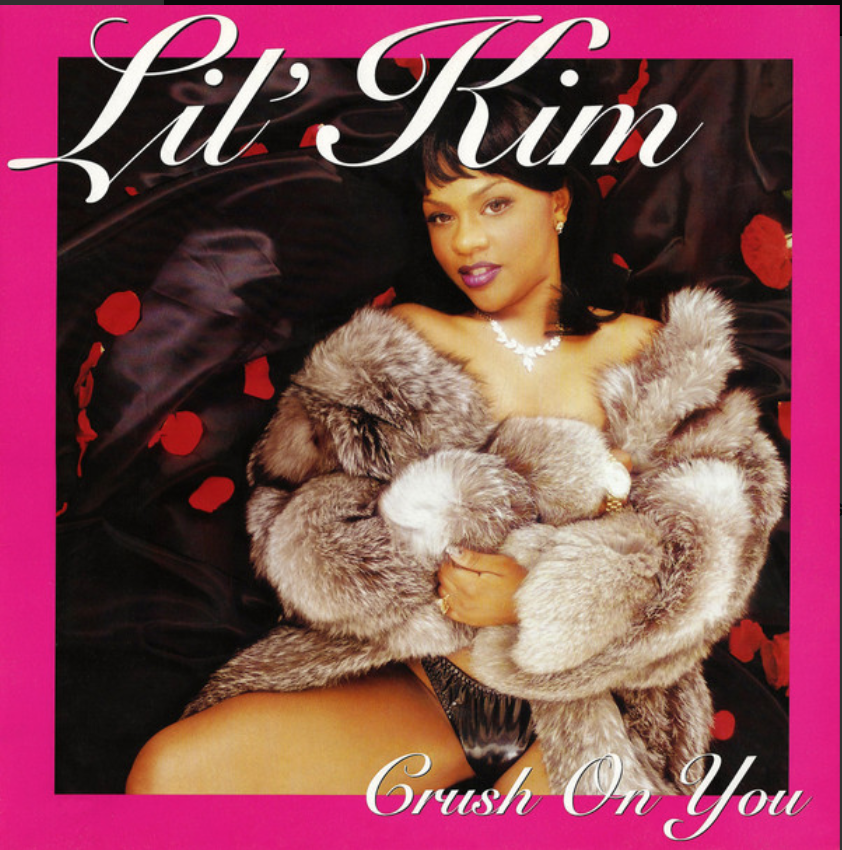

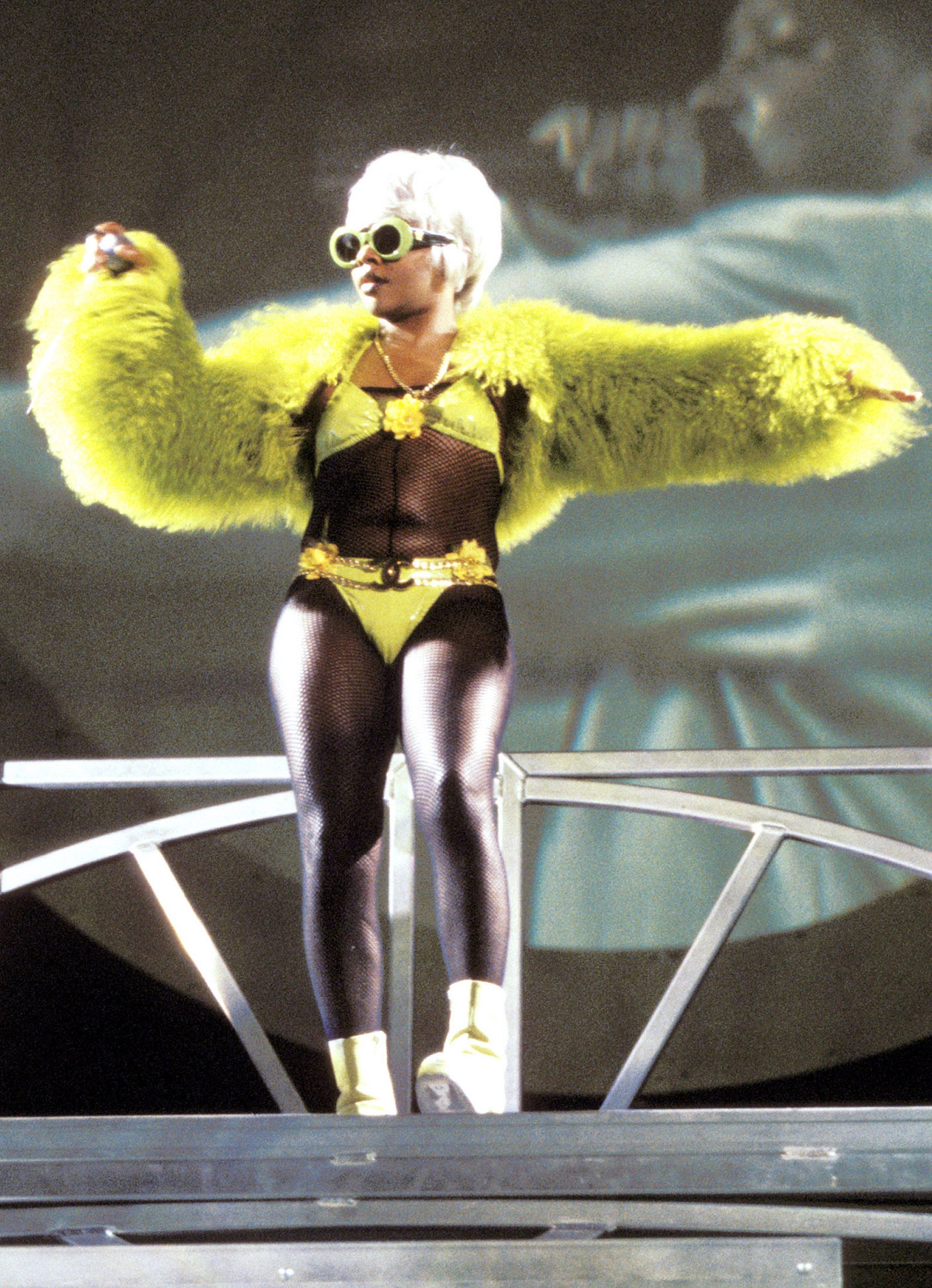

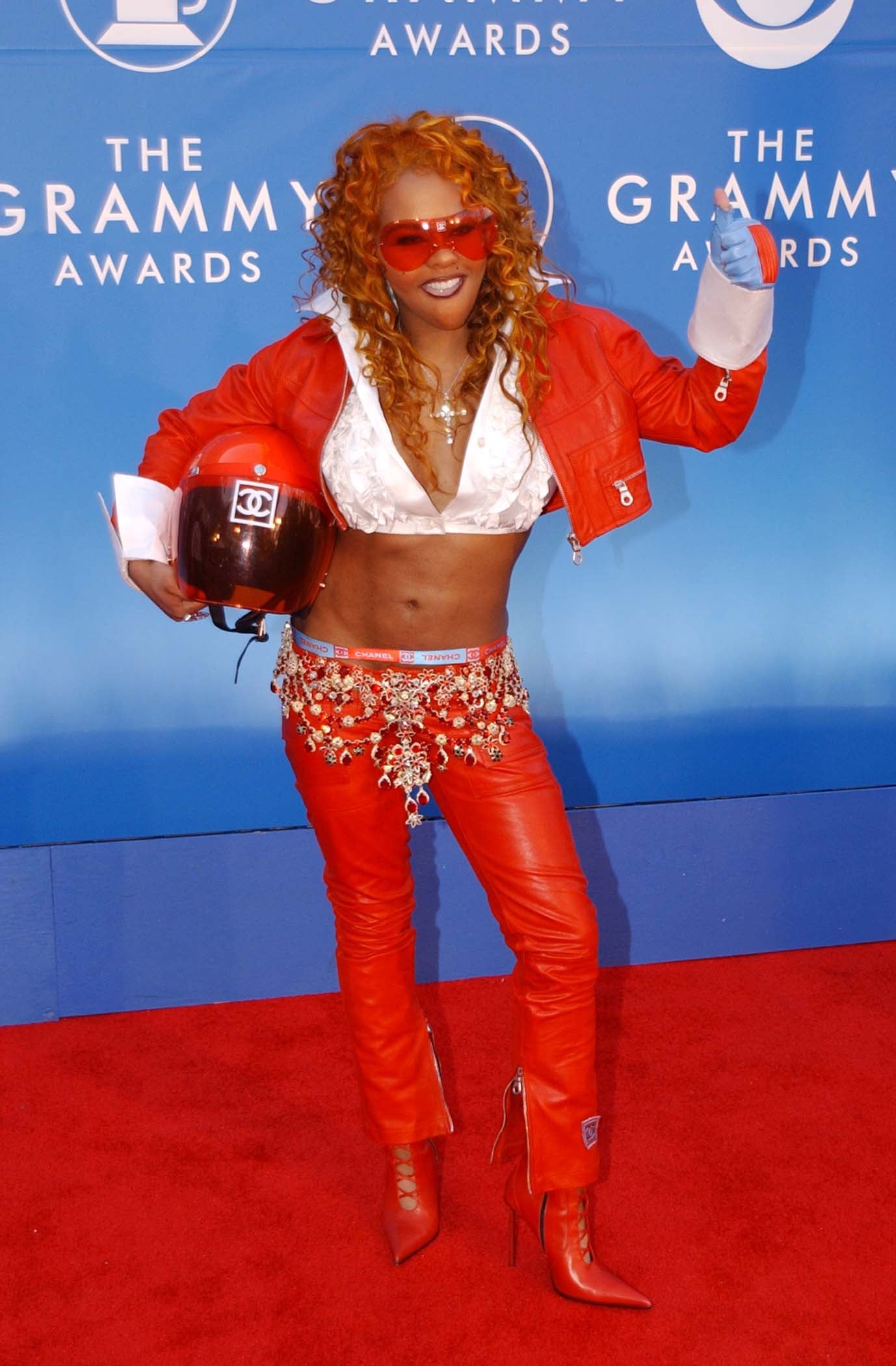

Lil’ Kim’s or Kimberly Denise Jones’ 1997 music video for ‘Crush On You’, the second single from her debut album ‘Hard Core’ is emblematic as a turning point in both fashion and hip-hop, Jones represented a trend of reclamation within the relationship between feminine voices and rap. The four-minute video consists of four ostentatiously coloured rooms and dancefloors, alternating between the primary colours blue, green, red and yellow. Lil’ Kim, featuring artist Lil’ Cease and more than a dozen extra dancers concurrently change outfits depending on the background colour, Kim wears an assortment of provocative garments like bikinis, fur coats and matching coloured wigs, whilst the dancers also wear bikini tops, crop tops and tiny shorts. The aesthetic garment choices of Lil’ Kim and her stylist Misa Hylton assisted the image of Kim as a ‘sexual entrepreneur’ within nineties hip-hop culture. Materialistic and hyper-sexualised images in rap videos reflected endemic racism in contemporary society, as well as the widespread misogyny towards women in hip-hop, however, the ‘Crush On You’ video subverts expectation of sexual objectification and alternatively presented ‘a subtext of women’s empowerment and solidarity’ within the male-dominated industry. African American feminist and civil rights activist Audre Lorde wrote: ‘Sexuality is a component of the larger construct of the erotic as a source of power in women. Lorde's notion is one of power as energy, as something people possess which must be annexed in order for larger systems of oppression to function. Sexuality becomes a domain of restriction and repression when this energy is tied to the larger system of race, class and gender expression.’. Lorde expresses her contemplation that embracing female sexuality leads to a consequential shift towards combating misogyny and oppression, a parallel to the artistic manifesto of Lil’ Kim.

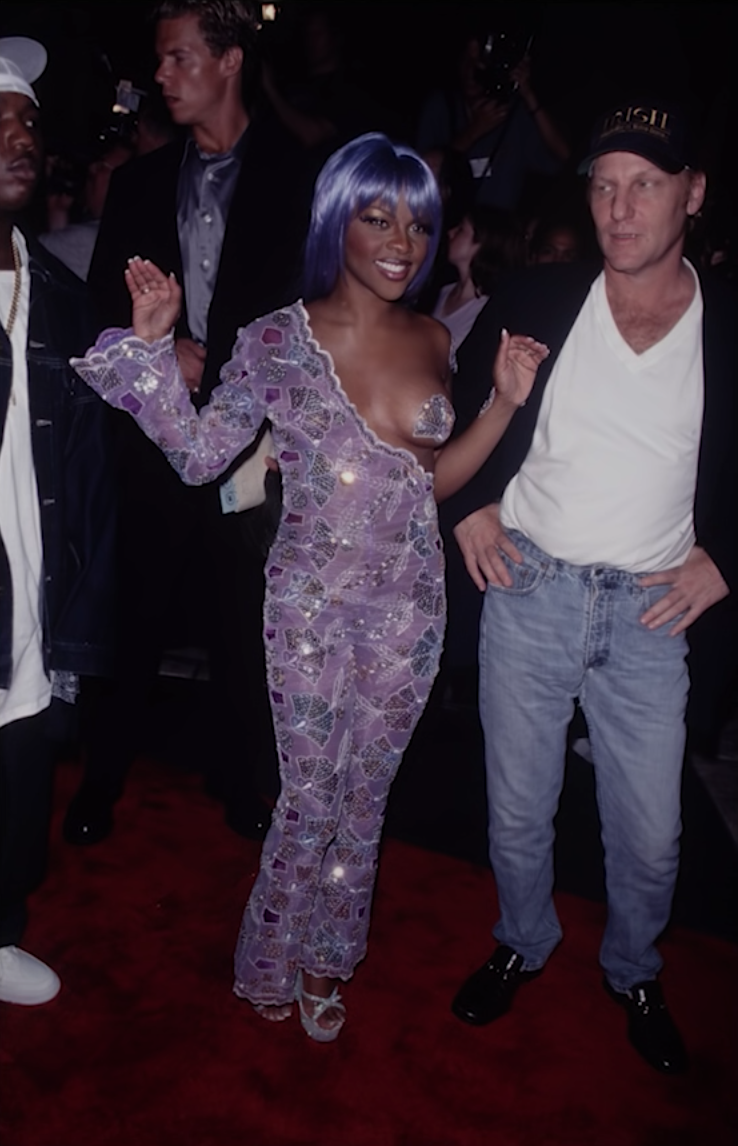

Lil’ Kim’s infamous look for the 1999 Video Music Awards ceremony featured a ‘breast-baring purple jumpsuit and glittering sequins pasty’ it is another salient example of the rapper using fashion to control a societal-wide hyper-sexualised image of femininity in hip-hop culture. Hylton, as aforementioned also designed and assembled this piece from ‘a fabric used for wedding saris’, she argued the maximalism and provocativeness of the outfit matched Kim’s unassailable hyper-feminine persona. In her own words: ‘The fashion statement Lil’ Kim made is the epitome of authentic style, courage, and standing in your power” she continued ‘Everyone had a front row view to see the beauty of being totally free in your artistic expression’.

In Benjamin’s ‘Arcades Project’ he writes: ‘Every fashion is to some extent a bitter satire on love; in every fashion, perversities are suggested by the most ruthless means. Every fashion stands in opposition to the organic. Every fashion couples the living body to the inorganic world. To the living, fashion defend the rights of the corpse. The fetishism that succumbs to the sex appeal of the inorganic is its vital nerve.’. Despite the book being written in the early twentieth century, the writing corresponds with Lil’ Kim’s desire to oppose male sexualisation of the female body by pushing the boundary of her wardrobe so far, eccentricity becomes celebrated and normalised and a part of the modern fashion canon.

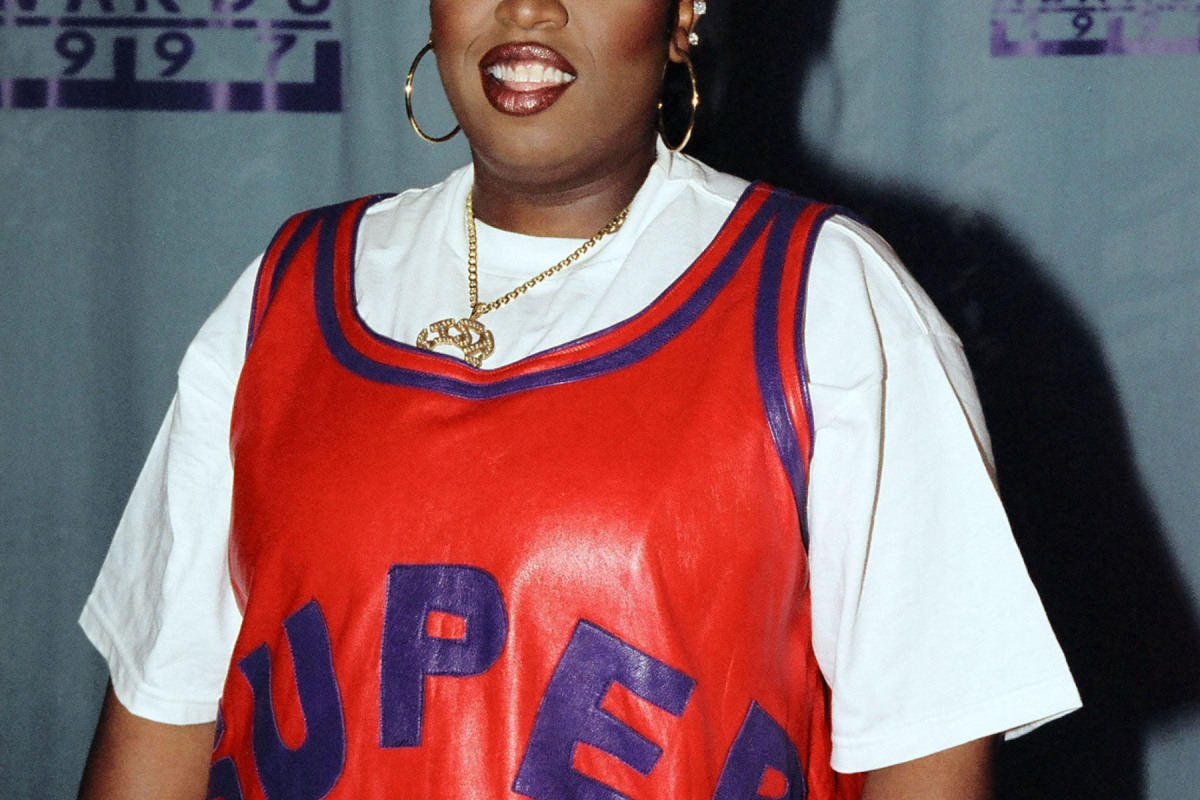

Missy Elliott’s ‘The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly)’ stands as salient example of Elliott’s career-long objective of threatening ‘heteronormative, patriachal systems that maintain men’s dominance in the rap industry’. In the video Elliott wore ‘an oversized thick rubber black trash bag, large gold hoop earrings, and dark-red sunglasses attached by a gold headpiece’, although not inherently revealing compared to other relevant female rappers, the outfit still demonstrated sexuality as power, letting ‘her unique music style speak for itself rather than exploit her sexuality to get media and audience attention.’. The majority of garments worn by Missy Elliott throughout this video and her career are non-revealing, she leans on matching tracksuits, sports jerseys, trainers and leather jackets to portray her femininity. Additionally, ‘she continues to rely on close-ups of her face interspersed with some choreography... [and suggests that] this type of female perspective portrays female fantasies of the overthrow of male domination and the forming of alliances among women.’.

Importantly, choices made in regards to garment design and presentation hold implications for women, since the advent of disregard to the corset through to the present day. However, fashion possesses additional consequences for African American women, ‘clothing choices and accessories function in a variety of ways, from establishing the wearer’s status (e.g. designer labels) to attracting attention from others (e.g. skank chic)’. Professor Noliwe M. Rooks, asserts that ‘fashion choices reinforce cultural associations about African American women and sex’. Appropriate clothing aimed to refute and rebut against stereotypes which follow gendered and racial oppression ‘from cultural associations with rape and sexual availability’ analogous with African American women.

The contemporary urban fashion landscape has been appropriated in alternate ways by female rappers like Queen Latifah and Lil’ Kim, the enclaves are within different epochs and locations of hip-hop culture, the new contemporary narrative uses “hoods, high heels, and couture” in fashion to counteract the archetypal ‘video ho’ in the hip-hop cultural canon.

Patricia Hill Collins in ‘The Social Construction of Black Feminist Thought’ wrote about the meaning of Black womanhood, or sisterhood in galvanising and supporting community to resist racial and gender oppression. She says: ‘Within African American communities, Black women fashioned an independent standpoint about the meaning of Black womanhood. These self-definitions enabled Black women to use African-derived conception of self and community to resist negative evaluations of Black womanhood advanced by dominant groups’. The image of female rappers Lil’ Kim and Missy Elliott sat together, both wearing garments made by Misa Hylton, Elliott in a matching leather and denim suit and Kim wearing a tiara and revealing sparkly, feathered dress, demonstrates how different methods of portraying femininity through fashion in hip-hop culture can alleviate stereotypes and work towards a singular objective.